PLASTIC SURGERY NEWS

Singapore Association of Plastic Surgeons

Dear friends,

Welcome to Plastic & Aesthetic Surgery Meeting 2022! We are excited to have the meeting back to an in-person format, allowing for greater interaction and discussion. The theme for this year is blepharoplasty and periorbital rejuvenation, an extremely pertinent topic in Asian aesthetic surgery. As they say, the eyes are the windows to the soul! We are honored to have distinguished keynote speakers Professor Cho In-Chang from Seoul, Professor Lai Chung Sheng from Taiwan, Dr Woffles Wu and Dr Wong Chin Ho from Singapore. These luminaries have published widely on blepharoplasty and periorbital rejuvenation, and are regarded as leading exponents in this area. Please join us for this year's meeting on the 17th of September 2022 at the Grand Copthorne Waterfront, Singapore, and we promise a stimulating meeting with lots of learning and fellowship!

Yours sincerely, Dr Adrian Ooi and Dr Gavin Kang

Introduction

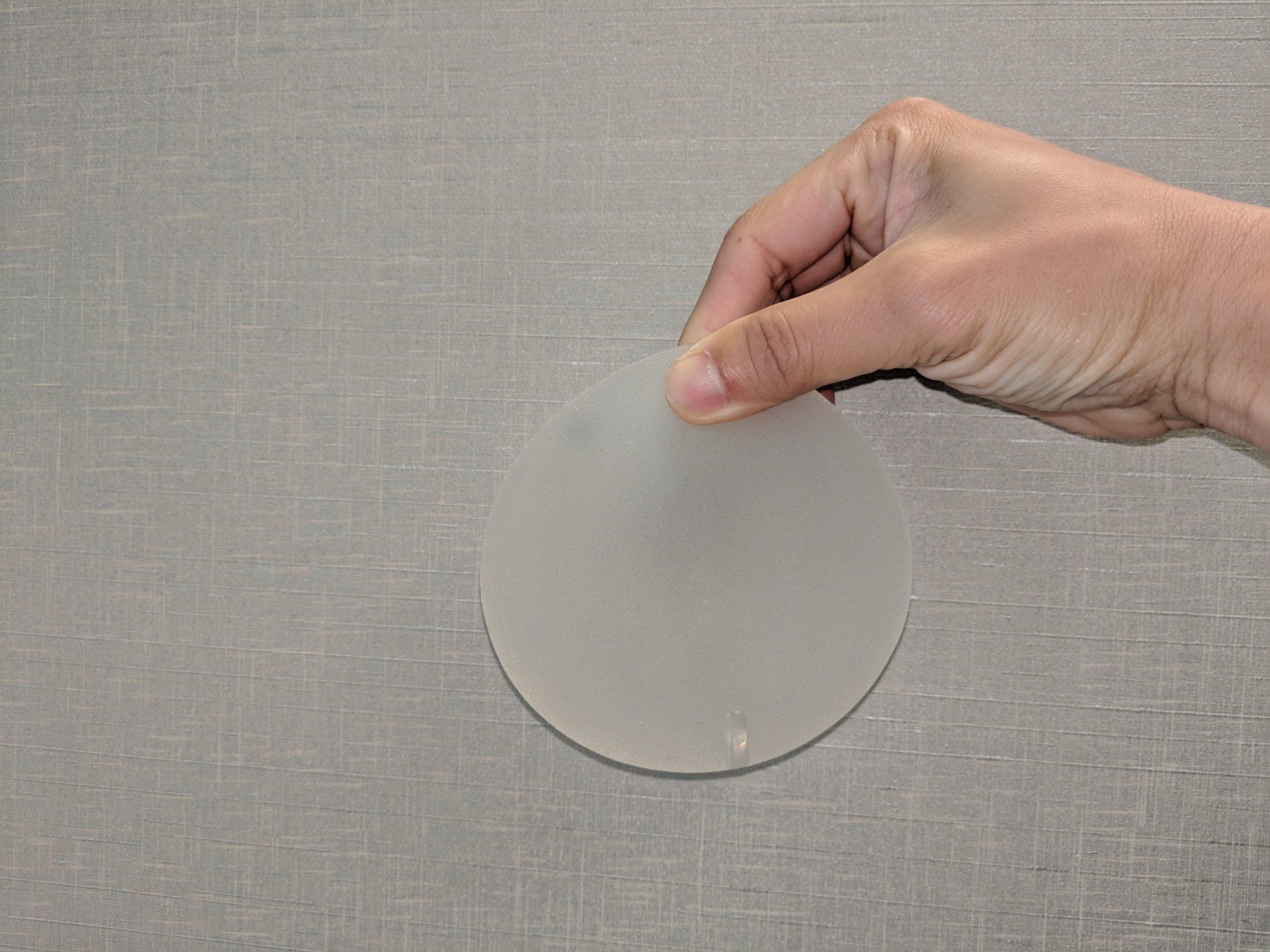

Breast implants are commonly used for cosmetic augmentation as well as post-mastectomy cancer reconstruction. Breast implants are composed of a silicone shell, filled with silicone gel or saline. Historically, smooth-shelled implants were used in the 1970s and 1980s. In the late 1980s, textured-shell breast implants were introduced to reduce the incidence of capsular contracture (internal scar formation), and their use significantly increased in the 1990s 1,2.

What is BIA-ALCL?

BIA-ALCL is a rare peripheral T-cell lymphoma that was first reported in the medical literature in 1997 3, and more than 300 cases of BIA-ALCL have been reported to the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 4, mostly occurring in patients who have undergone textured-surface breast implants. It is thought that development of BIA-ALCL is a complex process involving many factors, including bacterial biofilm growth, textured implant surface, immune response, and patient genetics 4. The estimated incidence of BIA-ALCL ranges from 1 case per 30,000 4,5 to 1 case per 4,000 6. Because this is an uncommon disease, data is still being accumulated and medical knowledge on this topic continues to evolve.

How does BIA-ALCL present?

The most common clinical presentation is a late peri-implant effusion, which manifests as breast enlargement more than one year following the breast implant surgery. Other less common symptoms include a breast mass, enlargement of the lymph nodes of the axilla, or “B-type symptoms” (fever, night sweats, lymph node enlargement, and fatigue). The average time to onset of BIA-ALCL after implantation is 10.7 years 4,5. BIA-ALCL may affect patients with either silicone- or saline-filled implants.

BIA-ALCL may be diagnosed on ultrasound or MRI scan, in conjunction with the use of image-guided needle fluid aspiration or biopsy. If BIA-ALCL is confirmed, further investigations may be required to determine the stage of the disease so as to guide appropriate treatment.

How is BIA-ALCL treated?

Most cases are localized (early) disease, which often follow an indolent course, and are cured by implant removal and complete excision of the peri-implant capsule, without further intervention 7. After complete excision, regular surveillance with clinical examinations and imaging investigations may be required. Patients with more advanced disease, including patients with a tumor mass, lymph node involvement, and/or distant spread, may require chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both 4.

What do I do if I already have a textured breast implant inside me?

The US FDA states: “If you have breast implants, there is no need to change your routine medical care and follow-up” 8. Additional screening or removal of implants is not required for asymptomatic women 8,9. The FDA continues to affirm that “BIA-ALCL is a very rare condition” 8. Should you experience any of the symptoms described above, do arrange for a consultation with your plastic surgeon.

The History and Safety of Breast Implants

In the late 1980s, early reports appeared in the medical literature describing a possible association between silicone-gel filled breast implants and certain autoimmune diseases, such as scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. In 1992, the United States FDA restricted the use of silicone breast implants to reconstructive purposes or clinical trials only. Subsequent publications were later unable to establish an association between silicone-gel implants and autoimmune disease 10 and the implants were once again made available for aesthetic purposes in 2006 7. This is an example of how plastic surgeons, regulatory authorities, the device industry, and patients work together for post-market device surveillance, ensuring short- and long-term patient safety as a common goal.

Conclusion

There has been recent association of textured breast implants with BIA-ALCL. Research will continue, and theories, data and clinical recommendations will evolve. Breast surgery involving implants remains a safe procedure in the hands of trained plastic surgeons and appropriately selected patients, regardless of whether it is performed for aesthetic or reconstructive purposes.

References

1. Lazzeri D, Agostini T, Bocci G et al. ALK-1-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma associated with breast implants: a new clinical entity. Clin Breast Cancer 2011;11(5):283-296.

2. O’Shaughnessy K. Evolution and update on current devices for prosthetic breast reconstruction. Gland Surg 2015;4(2):97-110.

3. Keech JA HR, Creech BJ. Anaplastic T-cell lymphoma in proximity to a saline-filled breast implant. Plast Reconstr Surg 1997;100(2):554-555.

4. Leberfinger AN, Behar BJ, Williams NC et al. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: A systematic review. JAMA Surg 2017;152(12):1161-1168.

4. Brody GS, Deapen D, Taylor CR et al. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma occurring in women with breast implants: analysis of 173 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 2015;135(3):695-705.

5. Doren EL, Miranda RN, Selber JC et al. U.S. epidemiology of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Plast Reconstr Surg 2017;139(5):1042-1050.

6. McGuire P, Reisman NR, Murphy DK. Risk factor analysis for capsular contracture, malposition, and late seroma in subjects receiving Natrelle 410 form-stable silicone breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg 2017;139(1):1-9.

7. Calobrace MB, Schwartz MR, Zeidler KR et al. Long-term safety of textured and smooth breast implants. Aesthet Surg J2017;38(1):38-48.

8. “Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL)”. 2017. FDA. US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/ImplantsandProsthetics/BreastImplant.... Accessed June 30, 2017.

9. “ASPS/ASAPS update breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) Quick Facts and FAQs”. ASPS/ASAPS. American Society of Plastic Surgeons/American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons. 2017. https://www.surgery.org/downloads/blasts/BIA-ALCL/. Accessed June 30, 2017.

10. Bar-Meir E, Eherenfeld M, Schoenfeld Y. Silicone gel breast implants and connective tissue disease – A comprehensive review. Autoimmunity 2003;36(4):193-197.

Released on 15 Mar 2019

The Singapore Association of Plastic Surgeons, together with the Chapter of Plastic Surgeons, College of Surgeons, Academy of Medicine Singapore, is proud to announce the 4th addition of our annual scientific meeting. The conference has grown from strength to strength every year, with both local and regional participants having the opportunity to learn the latest in reconstructive and aesthetic surgery from internationally renowned plastic surgeons.

This year, the theme is 'Facelift, Fat Graft, Fillers', 3 'F's which are of paramount importance to any plastic surgery practice. We are delighted to confirm Dr Patrick Tonnard from Ghent, Belgium, as one of our keynote speakers. Dr Tonnard is widely known as the creator of the MACS lift, as well as his microfat grafting techniques. Other speakers will be confirmed soon.

We invite all medical professionals involved in plastic surgery to save the date for this exciting meeting, to be held at the state-of-the-art conference venue The Academia, Singapore General Hospital, 18-19 Oct 2019. Please go to the conference website at www.pasm2019.com , to sign up for updates, which we will be providing very soon.

We look forward to welcoming you to sunny, beautiful Singapore!

Dear friends,

Welcome to Plastic & Aesthetic Surgery Meeting 2022! We are excited to have the meeting back to an in-person format, allowing for greater interaction and discussion. The theme for this year is blepharoplasty and periorbital rejuvenation, an extremely pertinent topic in Asian aesthetic surgery. As they say, the eyes are the windows to the soul! We are honored to have distinguished keynote speakers Professor Cho In-Chang from Seoul, Professor Lai Chung Sheng from Taiwan, Dr Woffles Wu and Dr Wong Chin Ho from Singapore. These luminaries have published widely on blepharoplasty and periorbital rejuvenation, and are regarded as leading exponents in this area. Please join us for this year's meeting on the 17th of September 2022 at the Grand Copthorne Waterfront, Singapore, and we promise a stimulating meeting with lots of learning and fellowship!

Yours sincerely, Dr Adrian Ooi and Dr Gavin Kang